Concrete Roman sewer (cloaca del foro) Image source: https://tinyurl.com/myson37

For centuries, human beings have blended water, ash, and silicates to produce mortars to bind building materials together or to form concrete masses for structures. Mortars were formulated with low-magnesial lime to join pipes supplying water across Asia Minor and Cyprus; in Ionia, the construction was so impermeable that pipes carried drinking water through canals. Techniques such as adding aggregates like crushed rock or sand to increase stability were used by the Romans to build aqueducts and other works; this knowledge was lost with the end of the Empire. Egyptians, Persians, Indians, and Native Americans added gypsum (which inhibits flash setting, a condition where the concrete because too rigid too fast and produces a great amount of heat) to their mortars, however the Greeks and Romans did not and its use did not come to Europe until the seventh or eighth centuries. By the Middle Ages, improvements in water resistance came when builders in central Asia added sour camel’s milk to their mortars and in England where builders used Cheshire cheese. Egg white was used for the same reason during the building of the Charles Bridge in Prague (1357-1402).

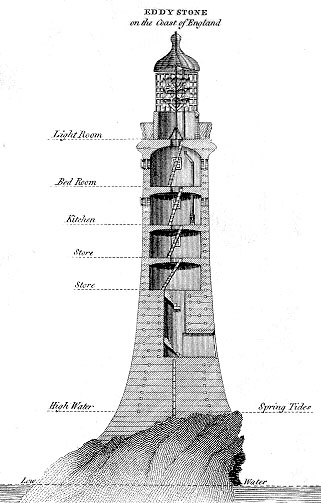

Smeaton’s Lighthouse, also known as the third Eddystone Lighthouse. Image source: https://tinyurl.com/nsxy987

By the time the Industrial Revolution arose, there was a huge need to build large industrial buildings, as quickly and cheaply and durably as possible as well as move water and other fluids in large quantities. The answer was a new kind of cement. British civil engineer John Smeaton was commissioned to build a new lighthouse on a reef along a strategic shipping channel in southwest Britain. Smeaton used “hydraulic lime” which sets under water. The lighthouse was under construction from 1756 to 1759 and remained in operation until 1877 when the rocks beneath it became unstable.

One interesting aspect of cement is that while people knew how to make and use it, they did not understand why it worked or which chemical reactions caused the properties that achieved the desired results. Smeaton’s experiments led to the discovery of how much clay the various components contained was the only factor in making them hydraulic.

Several men patented or marketed products called “British cement” or “Roman cement,” but it was an English stonemason, Joseph Aspdin, who first employed the term “Portland cement” perhaps to evoke the cachet of stone on the Isle of Portland. Aspdin first marketed Portland cement in 1824, and by 1843, his son William used the name “Patent Portland cement,” in spite of the fact that he did not have a patent. By 1853, William Aspdin moved his operations to Germany where the cement was fired in an endless kiln. The German standards organization eventually made this recipe the standard Portland cement, known the world over as ‘OPC’, Ordinary Portland Cement.

London Metropolitan Sewer at Rosebery Avenue.

Image source: https://tinyurl.com/Subterranea-Britannic

Even Thomas Edison tinkered with Portland cement. Using his process, he claimed, contractors could pour an entire house using only a few men and a cement mixer, virtually eliminating the need for carpenters.

Modern cement was crucial to urbanization and industrialization. Transportation improvements such as canals, railroad foundations, and city streets flourished because of modern cement.

![Gatun Lock - End of the Day [1912] Joseph Pennell, (1857-1926). Image source: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/00649767/.](https://janetm88.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/gatun-lock-1916.jpg?w=620)

Gatun Lock – End of the Day [1912] Joseph Pennell, (1857-1926). Image source: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/00649767/.

Bibliography

“Houses of Cement,” Los Angeles Times, June 30, 1901. Accessed 31.01.2014

Mabry, James C. “The United States Portland Cement Industry from Domestic Supremacy to Foreign Domination.” PhD diss., Columbia University, 1998.

Nasvik, Joe. “Flash Set and False Set.” Concrete Construction (blog), September 1, 2000. Accessed 2.2.2014. http://www.concreteconstruction.net/concrete-setting/flash-set-and-false-set.aspx.

Sutherland, R. J. M., Dawn Humm, and Mike Chimes. Historic Concrete: Background to Appraisal. London: Thomas Telford, 2001. Google Books, http://books.google.com/books?id=GTjW1lZeYwgC&dq=John+Grant+of+the+Metropolitan+Board+of+Works&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Accessed 12.02.2014

Wikipedia contributors, “Concrete,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concrete. Accessed 12.02.2014

———, “Eddystone Lighthouse,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eddystone_Lighthouse. Accessed 12.02.2014.

———, “Portland Cement,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portland_cement. Accessed 31.01.2014

Znachko-Iavorskii, Igor, and Henry Leicester, translator. “New Methods for the Study and Contemporary Aspects of the History of Cementing Materials.” Technology and Culture 18, no. 1 (Jan. 1977): 25-42. Accessed 31.01.2014.